In a Crip Time and Place

Robin Eames

In a Crip Time and Place, narrated by Robin Eames

I meet Cynthia in the park after a postgrad history conference. We couldn’t find an accessible restaurant for the conference dinner, so we are sprawled around on the grass sharing a six pack of cider. Cynthia sees my wheelchair and wanders up to say hi. She has an infectious grin and a zebra-patterned cane. Afterwards someone asks if we know each other; I say no we’re just disabled.

When I pass other wheelchair users in the street we brighten up, nod or smile to each other. If we’re catching the bus together inevitably we end up chatting across the aisle, comparing tech like dads at a BBQ. Monotube or dual tube, 4” or 5” castors, specific degrees of negative camber, external motor or motorised wheels. Sometimes this happens with people using other kinds of mobility aids. I can often tell when someone is using a crutch because of a temporary injury, because they never meet my eyes. As if they’ll catch something if they look at me too long or come too close. I am the thing they are afraid of becoming, the worst case scenario.

I love when disabled strangers approach me, but I hate it when nondisabled strangers do the same. Usually the first thing they say is something along the lines of ‘what’s wrong with you?’ or ‘what happened to your legs?’. I have a litany of responses to this. If I feel generous I say ‘why do you ask?’, if I am tired or in a hurry I say ‘termites’ or ‘dropbear attack’. I’m not opposed to talking about my disabilities with people I don’t know, but if it’s all they want to know about me then they don’t deserve to have their curiosity sated.

Cynthia is working on a project called Animate Loading, a performance piece about movement in public space choreographed by Riana Head-Toussaint. I’d met Riana a few years ago in Newcastle, at the afterparty for the National Young Writers Festival, This Is Not Art and CrackX. In a crowd full of tipsy bipeds she was the only person at my height. I won’t say that our eyes met across the room, but I remember how her eyes lit up; she was luminous. It was one of the first times in my life that I’ve been in the same room as another wheelchair user.

At the party, I lose track of Riana immediately but spend the rest of the night dancing with new queer friends, poets and musicians and memoirists. Someone comes up to me and tells me I’m brave. I am speechless. My new friends lose it; one yells at him, another tells me later that they are often told the same thing for being visibly trans. 'I’m not brave, I’m just a drunk bitch at a party', they declare. Me too.

Animate Loading (2022)

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Run Time: 75 minutes

Concept, direction, choreography and sound design: Riana Head-Toussaint

Performers/collaborators: Leo Tsao, Tom Kentta, Natalie Tso, Bedelia Lowrencev, Jeremy Lowrencev, Savannah Stimson

Outside Eye and Access Support: Imogen Yang

Access: level ground and lift access between floors, audio loops, wheelchair accessible bathrooms with adult change facilities, portable seating, wheelchairs and mobility scooters available for temporary use.

COVID safety: Partly indoors and partly outdoors. Masks encouraged.

A reimagining of public space and its uses. Animate Loading is an evolving site-responsive work, involving a group of people with different movement languages and embodied experiences (politicised in various ways due to race, disability, sex, gender and movement mode) entering a location, traversing and interacting with it. It’s a performance, but also a socio-political intervention. Their movement foregrounds the complex negotiations that often go unnoticed between bodies and the built environment, in order to reconfigure interactions with place, architecture and each other.

I come to see Animate Loading in its second iteration, as part of the opening launch of the new South Building of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. (The first takes place on a rooftop carpark in Parramatta, the third in the post-industrial structure of Casula Powerhouse.) I drag along a dear friend L who is about to leave the country for several months.

Cynthia has borrowed a mobility scooter from the art gallery, and operates it like a pro; I’m impressed. She has seen the show every night, taking different routes every time to view different sections from various angles. She asks if she can tag along with me this time, I say of course, and introduce her to my friend.

The performance begins before I notice it, with no preamble and no hushing or brightening of lights. Performers emerge from the crowd and begin to trace the railings, climb the benches, stretching and tumbling without urgency. I notice the audience beginning to look at each other with new interest, wondering who among us is part of the performance. A young man in a green shirt starts skateboarding up and down the gentle incline of a ramp. I am thrilled: the movement is so familiar to me, so recognisably disabled. L is mortified: the skateboarder is a former housemate.

The performance continues and I trail around following the dancers. Some writhe on the floor, circle around making trick shots with a basketball, topple slowly against the walls. I notice someone licking a glass window. I run into Riana in the lift, as the dancers spill out onto the escalators.

Towards the end of Animate Loading, the dancers move from the interior of the ground floor to the outside courtyard. By this point I am following Riana, and there is a moment where she and I sail together out of the gallery, ahead of the crowd. We move in wordless synchrony.

I interrogate her after the show, asking about her practice and the mechanics of the performances. She says she attached little roadie mics to her wheelchair to capture the sound of her tyres scraping across sandstone, swishing grass, water rushing between the rocks, the wind through her wheels. She wanted the show to feel punk, radical, to push against constraints and reclaim space. It takes a new form with every iteration, always bringing elements of previous shows into the new ones, constantly transforming and transformative.

As the performers draw on their diverse lived experiences, movement languages and bodies to build their own ecology in the space, their presence and movement functions as a call to action. To disrupt, resist and change our relationship with public spaces, and with each other within them.

– Riana Head-Toussaint

During lockdown I take up birdwatching and go quietly insane. I lose muscle mass. My pain gets worse. I begin to tell time more by the phase of the moon than the day of the week.

Suddenly I am flooded with commissions. Online poetry slams (usually held in venues I can’t get into). Zoom workshops for projects having to come up with new uses for grant funding. I haven’t written a poem in months. Nothing feels urgent enough. I write copy for mutual aid groups and the Disability Justice Network. I try to pour my frantic misery into something useful.

I am commissioned by the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art to write an essay about the work of artist Sam Petersen, for the exhibition Overlapping Magisteria. I am generally pretty skeptical of modern installation art. A few minutes into our conversation, Sam has utterly won me over. The artwork is a site-specific sculpture, pink plasticine creeping through the steel-walled gallery foyer. Sam is a wheelchair user who uses AAC to communicate. I know immediately that the artwork is a deeply, beautifully disabled response to a hostile world.

Disabled Otherworlds (excerpt)

The imposing urban architecture has its edges forcibly softened and made strange. Technology turns biomorphic, organic. The building, like the disabled body, becomes a cyborg amalgamation, its meanings altered and repurposed…

The conflict between the organic and inorganic is one of many conscious ambiguities. Androgynous forms move through liminal territories and subvert binary entry points, destroying and recreating the site – or as Petersen puts it, quite literally ‘fucking the building’. The plasticine marked with fingerprints is simultaneously alien and intensely personal. Petersen is absent but present in all the spaces beneath and between, invisible and hypervisible. Plasticine, Petersen says, is ‘a great recorder of touch, and then that touch could be put on other things’.

I start writing poetry again because Andy Jackson asks me to join a collaborative project of disabled poets. I remember how to feel joy. I write several poems in collaboration with several different poets, all incredible writers who bring a range of insights, artistic styles, and chaotic disabled energies to the work.

One poem is an exquisite corpse, an assemblage piece with Michèle Saint-Yves, in which we trade stanzas riffing on the Questing Beast of Arthurian myth. Another is a duet with Jasper Peach: a call and response, reusing lines and phrases with a different spin. Another is a crip triptych: three poems about wheelchair joy, written by myself, Gaele Sobotte and Kerry Shying, designed to be read together. Kerry’s poem is printed out and stuck to my fridge. My own contribution to the criptych is called Joyride:

Joyride (excerpt)

Listen I said I'm hell on wheels

burning up the bitumen

I'm that vroom vroom mthrfckr

that Tilite street fighter

that acid green that sleek freak

lean mean meme machine

I'm that speed demon born 2 ride

that deadly sin that crip pride

that battleground that unsound

that rebel yell I'm hellbound

I'm underground I'm thunder

& lightning I'm frightening bipeds

w that BEEPBEEP that tyre shriek

that too fast too young

I'm well hung high-strung…

For Rabbit Journal’s ‘Collaborations’ issue, I am one of five (!) poets weaving together a beautiful behemoth of a poem, alongside Beau Windon, Andy Jackson, Michèle Saint-Yves and Ruby Hillsmith. Andy speaks to the power of disabled collaboration:

how when you know the other person "gets it", you can write with honesty and courage, and also at the same time the process really requires listening, respecting the differences, so the two voices can be at home together. I'm also thinking of how I've been able to surprise myself, find things in my voice I wouldn't otherwise have found.

We write it in pieces, one stanza at a time, employing several different poetic techniques: tapestry, Bouts-Rimés, chain poetry. The thread of emails has over seventy entries, spanning months. Andy corrals the project with deft, efficient gentleness, and somehow the whole thing comes together. The resulting poem is called ‘Coalescent’. It’s magnificent.

In poetry I can express things that I struggle to articulate otherwise. Disabled poetry has its own languages and styles, and its own speeds and landscapes. Something about the fragmentation of poetry allows me to read and write slowly, with purpose, or quickly, before my fatigue wins out over my fascination. Every word is heavier. In poetry I can step outside of the world and imagine another one. In prose I have to explain the journey in between.

*

I miss the dancefloor. When I first started using a wheelchair I thought I’d never be able to dance again. My first attempt at going out dancing as a wheelchair user is fraught. The venue doesn’t have a lift, and the security guards carry me down a long flight of stairs. A man pats my leg and spills his drink on me. A woman approaches me and tells me that she cried when she saw me because her son is autistic.

Despite this I love it. Dancing with my wheelchair is fluid and euphoric. I stay out for hours.

It takes a while for me to learn how to dance on wheels. Bipeds rarely give me enough space, and rarely anticipate the directions I will move in. I learn to keep half an eye over my shoulder so that when I roll backwards I won’t plough into anyone. Most dance venues in Sydney are not wholly wheelchair accessible. If I can get through the door I still might not be able to get to the bar. Often the biggest issue is whether they have an accessible bathroom. Some bars have an accessible bathroom but keep it locked, or use it for storage, or the lock is broken and has been for years. I wish that venues would just list this info on their websites. It’s exhausting keeping a mental catalogue of all the places I can get into, and of their caveats.

For a long time the only regular queer party in wheelchair-accessible venues with Auslan interpreters and quiet spaces is Unicorns, run by Delsi Cat. I hone my amateur craft. I enter a dance battle and narrowly avoid battling my ex. Instead I end up on stage with two friends and have one of the best nights of my life. I quickly realise that I don’t know as many of the lyrics to YMCA as I thought I did. I lose and I can’t stop laughing.

Robin dancing on stage with T, who is using a cane and lip-syncing like a pro, and A, an Auslan interpreter who is signing along to the music at Unicorns, 2019.

On a different dancefloor I hole up in a corner with Deaf friends and friendly strangers. The music is so loud that I can feel the bass vibrating up through the frame of my chair. My friends are signing too quickly for me to follow them. At this point I have only taken one Auslan class and clearly haven’t practised enough. I am introduced to someone. I ask them to fingerspell and they acquiesce, but it is still too fast for me. I make the sign for ‘slow’, stroking my right hand over the back of my left, pulling an apologetic face. They laugh but slow down.

Auslan sign for 'slow', from Auslan Signbank

Later I realise that I had made the sign for ‘cat’.

Auslan sign for 'cat', from Auslan Signbank

In 2023 I read a poetry book written by a comrade, and then immediately write a fucked up poem called Leg Stories. I say ‘write’, but it feels like something deep inside me spat the poem out without much input from me. There’s one stanza that’s still clunky, an attempt to retell a horrifying anecdote from a friend. Her support worker kept banging her feet into furniture while pushing her wheelchair, and every time this happened she would scream from pain. And then her support worker wrote in her client file that she had developed a ‘behaviour of concern’, which was randomly screaming.

Every now and then I remember that story and have to sit with it for a moment.

Leg Stories (excerpt)

When you’re disabled everything is a behaviour. Try it & see. Personhood

is reserved for the healthy. Have you heard the one about Plato’s definition

of man? When asked how to define a human being he used the phrase

“featherless biped” & Diogenes of Sinope brought a plucked chicken

to Plato’s Academy, saying: “Behold: A man!” They updated the definition

but they kept the bipedal part. The Oxford English Dictionary says a human

is distinguished from other animals by superior mental development,

power of articulate speech, & upright stance. Guess I’m a plucked chicken.

The Air Between Us (2023)

Run Time: 20 minutes

Performers: Rodney Bell, Chloe Loftus

Rigging design and counterweight: Tym Miller-White

Music: Rhian Sheehan, Rikki Gooch, EVAC (ft. Rena Jones), Rival Consoles

Production team: Tribal Apes

https://www.sydneyfestival.org.au/the-air-between-us-digital

Two bodies aloft, tipping and spinning, connected and entwined, harnessing their differences and strengths into dance. A joyful aerial collaboration, The Air Between Us is created and performed by acclaimed New Zealand dancer and choreographer Chloe Loftus and award-winning Māori dance artist and wheelchair-user Rodney Bell.

The Air Between Us explores a meeting point; between two bodies in space, in perfect equilibrium, crossing boundaries of culture, with curiosity and play. Arriving at this place from diverse backgrounds and experiences, Chloe and Rodney explore our innate capacity to exist in symbiotic harmony. Like planets encircling around each other, magnetically pulled by each other’s energy, this is an inimitable and mesmerising performance.

In January, I convinced my (now ex-)partner to drive me into the city to see Rodney Bell perform as part of the City of Sydney Festival. We have trouble finding parking and get there late, catching the tail end of the performance: Bell and Loftus are intimately twining in mid-air, suspended by harnesses.

Bell’s wheelchair is compact, with orange tyres and no sideguards. They sink to the ground and he unclips his carabiner, spinning and wheelieing up on the grass. Loftus, still held aloft, traces his movements, takes his hand and uses her bodyweight to twirl him around and pull him along. She unclips herself and clips him back in. Their faces are close to each other, breathing the same air. He goes spinning up in a tight upward gyration, body lax; then he spreads out his arms. He looks like he’s flying. His shoulders are thickly muscled, and as he moves I am reminded of an osprey retracting its wings for a dive, then flaring them out to soar. Bell spins back down, one wheel touches the ground, then the other, and the performance is over.

I have been given this vehicle of dance, I have been gifted this vehicle of dance. I’m upside-down, my organs are moving, my body is swaying. I’m in touch with nature, I’m up in the air, I am where the birds live, what more could you ask for?

– Rodney Bell, quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald

Afterwards I wander through the MCA for a short time, alone. There are several other wheelchair users in the art gallery, enough to perturb the bipeds around us. I get even more confused sideways glances than I usually do. As I exit the lift someone says ‘another one?!’

When I leave the gallery I see Bell dancing with another wheelchair user over by the water, to the music of a busker. I trundle over to watch, as do a few other stray pedestrians. Rodney gestures for me to join them. I am embarrassed and overjoyed; I demur, but he gestures again, and I roll forwards. The three of us orbit each other, whirling and circling. The other two – Rodney and Sarah – are both professional dancers. I have no idea what I’m doing, but I’m having so much fun. I try to follow their movements and we fall into a rhythm. More people gather to watch us but for once I don’t mind the stares. We are in our own little world, and I smile so much my face starts to hurt.

Sarah and Rodney dancing; Robin joining them; Sarah and Rodney hugging; a group photo. Videograph: Sarah King.

Under Momentum (2018)

Run Time: 55 minutes

Performers: Laurel Lawson, Alice Sheppard

Choreography: Alice Sheppard, in collaboration with Laurel Lawson

Lighting: Michael Maag

Music: Joan Jeanrenaud, Michael Wall, Blue Dot Sessions

Access: ASL, rich spatial audio description via Audimance app, expanded accessible seating, haptic soundtrack interpretation, audience welcome to exit and enter during performance.

Under Momentum is a duet that celebrates the joys of continuous motion, the allure of speed, and the beautiful futility of resisting gravity. Laurel Lawson and Alice Sheppard of internationally-recognized disability arts ensemble Kinetic Light perform on a series of ramps designed by artist and design researcher Sara Hendren, creating a world of exhilaration, sensuality, and play.

Rodney is not the only wheelchair using dancer to take to the air. Alice Sheppard and Laurel Lawson of Kinetic Light Dance have been using aerials in their performance pieces for several years.

I first came across their work in 2018 and it hit me right in the gut. That was the world I ached to live in: a beautifully disabled realm of colour and light, a wild vision of wheelchair-using joy.

Quoted in the New York Times:

We’re thinking about access as an ethic, as an aesthetic, as a practice, as a promise, as a relationship with the audience.

– Alice SheppardAccess is not a separate thing. Access is the thing.

– Laurel Lawson

Disability Arts Ensemble Takes Access & Dance to New Heights: If Cities Could Dance

I often think of something Frida Kahlo wrote in her diary:

Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?

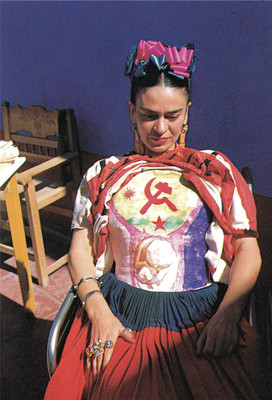

Kahlo was a wheelchair user and a Communist. She painted her own medical corsets and prosthetic leg, she smoked and drank like a fish, she often dressed as a man, and she slept with Trotsky. The commodified portraits of her on throw pillows and coasters look nothing like the Frida Kahlo whose work I admire. She has been corporate-sanitised into a colourful, generic symbol of the girlboss artist: all flowers, no politics or substance.

I read about dances and operas based on her life and they all have the same boring throughline about overcoming pain to produce vibrant art. They don’t dwell on her disability, and when they do it is usually derogatory. In the New York Times, nondisabled choreographer Anna Lopez Ochoa is quoted while rehearsing for “Frida” with the Dutch National Ballet: ‘Now, Frida pukes a butterfly, because she’s in a wheelchair, but she wants to be free.’

I am not an expert in the life of Frida Kahlo. But from what I have read of her writing, she wanted to be free of capitalism above anything else. She hated being trapped in bed and in hospital, and she hated being prevented from doing things. But I can find nothing suggesting she hated her wheelchair. When she painted herself as a wheelchair user, she painted her chair in loving detail, unobscured by her wide skirts. The wheel is a focal element of the painting, balancing out the portrait of her doctor frozen on the canvas behind her. The line of her back is tall and proud, a monarch on her throne. The axle rod is perfectly in line with her shoulder, the optimal position for self-propulsion. Her wheelchair doesn’t appear to have wheel locks. Without them she would have been in constant motion, never truly stopping, only pausing mid-flight.

Like Frida, bipeds look at me and think I am bound to my wheelchair. As far as I’m concerned I am no longer even bound to the ground. My wheelchair has freed me from the earth, from the endless pull of gravity, from my horrible bones. Now I am a creature of the wind, and my wings are my wheels.

Feet, what do I need you for?

Kahlo photographed seated on her wheelchair, painting her Self-Portrait with the Portrait of Doctor Farrill, 1951.

My freedom has limits. At my favourite local poetry night I text the staff to be let in, they bring out a manual ramp, I topple with intent over a couple of deep steps. If I need to go to the bathroom I can jump the step, but must rely on strangers to push me back up. If I get there late, I have to bully a whole corridor of people into moving their chairs up against the wall to give me space to get past. The poetry is worth it, but I wish getting in there wasn’t such a production.

I don’t really miss walking. When I do, it’s usually less about the walking itself and more about missing the casual ease of navigating the world as someone who could walk. I miss being able to go to the pub without calling ahead. I miss dating and making new friends without being seen as a fetish or a spectacle. I miss being able to get through every unlocked door. I miss being treated like a person by everyone I met.

None of what I miss is about my wheelchair or my disabilities. What I miss is living in a world that was built for me.

I am grateful, now, that I live in the world not built for me. It has radicalised me and taught me difficult lessons. I have learnt that people can be impossibly cruel and amazingly compassionate. I have learnt so much about solidarity and what it means to show up for others, about activism, about action, about love, about fighting for a better world to live in. I’ve learnt how to take things slow, how to speed down tricky hills really fast.

More than anything I’m grateful to be back in the world at all, and not stuck at home in bed.

If this world was not meant for us, then we’ll rebuild it in the shape of something new. A crip space, a disabled space, a Deaf space, a mad space, a neurodivergent space, a sick and ill space, a space of endless possibility. Art is not the sole path forward, but it’s one of the ways we can map out how to get there.