Social Bodies: full of history and experience.

Gabriela Green

Published May 2020

Response to Keir Choreographic Award Public Program at Carriageworks Sydney, 9 – 14th March 2020

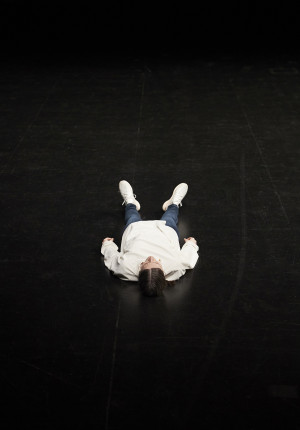

The choreographer William Forsythe once said ‘Choreography is not owned by dance alone’1 and Penelope Sleeps, an Opera demonstrates just that. This is the first work I see as part of the Keir Choreographic Award Public Program at Carriageworks. The work presents dialogue, music, opera and movement together as choreography. It begins with the performers lying down face up to the ceiling. The performance space and audience are both lit, and I am sitting on a cushion in line with the performers. Opposite the audience is an impressive seating bank deliberately left empty as if watching us. Edvardsen begins by acknowledging that we are all here together in this work: ‘I can’t believe how many people are here. I almost didn’t come.’

Penelope Sleeps is filled with space. There is little movement and no dance at all. There is space in the empty seating bank, between performers and audience, and in the silences between dialogue, music and opera. In every silent space I hear the audience shuffle. Our role as sound in the space completes the work and I feel this role is considered and important to Penelope Sleeps’ composition.

Mette Edvardsen, Penelope Sleeps, Carriageworks, 2020. Photographer: Zan Wimberley. Image courtesy of Carriageworks

As a dancer I find myself actively working to understand Penelope Sleeps in the context of dance. I’m drawn to the depth and perception between the performers, and how my body sitting on the floor wants to lie down with them. I do not see the opera singer Angela Hick’s face for almost the entire performance, but I see her body and I hear her sing, and so I imagine her face and my imagination is called into this performance. Edvardsen speaks of this work as a ‘… space to sink into and to be carried slowly away, a space to enter and listen………a space to become a part of and not just look at.’2 The movements in Penelope Sleeps suddenly seem not there to convey a message but to give space for the words to exist in a present body that is processing them with an audience. We are invited to find connection and meaning within this experience.

Towards the end, Hicks repeatedly sings ‘I am not sorry’ for a sustained period. The voice soothes my body creating an internal movement inside my ribcage. I think about all the things I am sorry for, my ribcage sinks and then I think about all the things I am not sorry for and my ribcage opens. This moment was captivating, it invited so much of myself into the work, including shame and pride and how they’re situated in my body. Even though I do not look at the audience at this moment I feel connected sharing this experience with them as the sounds of the music and Hick’s voice filled the space.

Two days later I attend Edvardsen’s workshop Choreography as Writing which begins with her instructing ‘today we will work as a collective’. Again, I feel considered. I learn about the other participants through their writing, their delivery, and how their bodies are positioned. Edvardsen’s workshop does not give us material, object or a product to work with, but rather a shared space over time for people to come together. The workshop begs to ask where is the work? and I understand that the role I play in this workshop is to be present with the other bodies in space and time. A social being developing practice in relation to others.

Once again, there is no dancing in Edvardsen’s workshop on choreography. She poses questions – how we perceive dance, how often dance is understood to be a visual experience – but is it really? This causes me to question how do we perceive text? Is Edvardsen’s work telling us something through its text or is it about an exchange between living bodies?

After the workshop I attend the Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine book launch. The book is written by performers from their experiences as living books in Edvardsen’s performance Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine at the Sydney Biennale in 2016.3 A living book is a performer who has memorised a book and reads it out to an audience member in a library. This again invites the question how do we perceive text? I find myself analysing the importance of having the story exchanged through a living body.

Philosopher Thomas Fuchs wrote in Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement of the concept of Leibgedächtnis (body memory). Leibgedächtnis explores how memory and experience are stored within our corporal bodies. Bodies react with other living bodies reshaping and learning constantly with each other and with environments. Fuchs writes ‘memory is based on the habitual structure of the lived body, which connects us to the world.’4 Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine allows for experience and memory to be shared through a story and through a social encounter.

Keir Public Program, Mette Edvardsen, Time Has Fallen Asleep, Book Launch, Carriageworks, 2020. Photographer: Rafaela Pandolfini. Image courtesy of Carriageworks

There is something interesting in Edvardsen’s living book process of asking performers to experience themselves as something other than human. On Leibgedächtnis Fuchs writes: ‘in order to see …..yourself differently, you have to act differently; have a different experience of interacting with the world…….. because that is how the body memory changes.’5 The work of becoming a living book, through the process of memorisation is placing a never changing story in an ever changing body. The living books’ ability to bring memory, experience and identity with them when they inhabit a book allows the book to change with others.

I later attend a morning dance class taught by Indigenous choreographer Vicki Van Hout as part of the public program. Van Hout is of Wiradjuri, Dutch, Scottish, and Afghan heritage. In this class Van Hout shares a collection of movement and techniques of different Indigenous traditional forms. The movements she explained have been inscribed in her body from her training at NAISDA Dance College. The movements are undeniably difficult for me to represent and through counts, direction, and transfers of weight I try to understand this way of moving as best as I can. I feel a clash between a Sovereign Aboriginal movement which carries within itself the most ancient memories of the world and my lived experience developed as a Chilean /Australian person who has trained in a Western tradition of dance.

Van Hout apologised in a humorous manner that she cannot help but bring into this space all the obligations, tensions and experiences she has in her body and likewise I cannot help but bring my living body that has travelled and developed through white, colonised ‘Australia.’ Van Hout wanted us to place our non-Aboriginal living bodies in the work of a Sovereign Aboriginal body – to better understand something we are not. I think of colonisation and its attempt to rob Indigenous people of their bodily autonomy.

Keir Public Program, Vicki Van Hout Morning Class, Carriageworks 2020, Photographer: Rafaela Pandolfini. Image courtesy of Carriageworks

Van Hout shares with us her choreographics tools exploring the idea of mapping. We map two points in the studio and travel from one point to the other using self-generated movements and sounds. I bring my memories of dancing in Chile to influence this task. For Van Hout the points are less important than the journey in between these two points, which she relates to the Indigenous concept of Songlines. My partner Warren Foster Jnr, a Djiringang man, explains Songlines to me as ‘the tracks that connect significant sites together, the journey we must take to understand how we got here today.’6

I reflect on this meaning and the experiences I had in the workshop: the feelings of disconnection I felt doing the movements Van Hout gave me and the feelings of comfort I found in the space that came from my own memory. I questioned myself – was the discomfort I felt doing traditional movements because of the genocide and colonisation that exist in the very foundations of place through which I carry my body everyday? Is this part of my body memory?

As activist and Gumbaynggirr man Gary Foley states ‘People have to look honestly at their own history. I don’t believe enough non-Aboriginal Australians know much about the reality of the Australian historical experience; about your history; about our history; about the two and where they connect. I think it is really important for people to learn that.’7

As an artist and activist I believe art belongs to everyone in a unique way. Van Hout and Edvardsen are both doing something very powerful through their work that connect us to the experience of ourselves, of each other, the other and the world. I leave with a question for my own practice. What do I need to do in my work to allow space for everything happening between ourselves, each other, and the world in order to acknowledge history, make meaning and connections?

Katrin Kolo, “Ode To Choreography”, Organizational Aesthetics 5(2016): 37-46

Mette Edvardsen, On the writing of Penelope sleeps

Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine, Performance Work, The 20th Biennale of Sydney, 15-19 March 2016, Newtown Library

Sabine C. Koch, Thomas Fuchs, Michela Summa, Cornelia Müller, Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement, (The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2012), 9

Thomas Fuchs, Roger Russell, Ulla Schlafke, Sabina Graf-Pointer, “A conversation about Leibgedächtnis (body memory)” Feldenkrais Research Journal Vol 5, (2016): 18

Warren Foster, Interview by Gabriela Green Olea, (Croydon Park, 7 April 2020)

Gary Foley, “For Aboriginal Sovereignty” Arena #83, 1988 http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/essays/pdf_essays/for%20aboriginal%20sovereignty.pdf

Biographies

Gabriela is a socio-political dance artist who works across many mediums, working with all people and within inclusive environments. As a daughter and granddaughter of a refugee family, her work responds to the ideas of cross-cultural identity and the transitional space of belonging to community and place. Gabriela choreographed a social project CPAL for the This is Not Art Festival in 2018. In 2019 she choreographed WHO WE ARE with dancers in regional NSW, living with and without disability mentored by Vicky Malin (UK). In 2020 Gabriela performed at the Sydney Festival in ENCOUNTER by Emma Saunders for FORM Dance Projects. Gabriela has residency in 2020 at Campbelltown Arts Centre as part of the DAIR Program with Ausdance, Dancehouse’s Emerging Choreographers Program and with Emma Saunders in FORM Dance Projects ‘Curated Program.

LIST OF PROGRAMS ATTENDED

Mette Edvardsen and Matteo Fargion, Penelope Sleeps, an Opera, 10 March 2020, Performance.

Mette Edvardsen, Choreography as Writing, 12 March 2020, Workshop.

Mette Edvardsen and Lizze Thompson, Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine, 12 March 2020, Book Launch.

Vicki Van Hout, Morning class, 13 March 2020, Workshop.