QUEER ATTACHMENT IN BATHURST

Paul Kelaita

Published November 2017

Review: The Unflinching Gaze: Photo media & the male figure, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery

The Unflinching Gaze: Photo media & the male figure is exhibited at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 14 October – 3 December 2017.

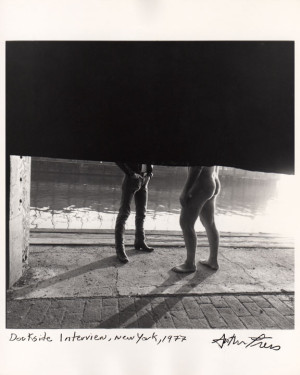

Two men stand about half a metre apart at a waterside beat in New York. We see only the lower halves of their bodies. One is in bulging jeans the other is naked, the small of his back and the curve of his butt glisten in the sunlight. This photograph is Arthur Tress’ Dockside Interview (1977) and is one of over 200 works in The Unflinching Gaze: photo media & the male figure.

The Unflinching Gaze is an ambitious exhibition that brings together photographs and video spanning 140 years drawn from collections around Australia and farther afield internationally. Richard Perram OAM, director of Bathurst Regional Art Gallery (BRAG) and curator of the show, explicitly frames the exhibition through his own position as an openly gay man with his own interests and his own ‘“queer” eye’ rather than as a comprehensive survey.[1] Paths can be traced through the exhibition on the erotics of gay attachment to sculpted bodies, to naked bodies, to dicks, to butts, to clothed bodies, to leather, to denim, to white men, to black men, to Asian men, to celebrity, to queer undertones in history, to strategies for navigating and surviving phobic cultures.

With an exhibition so large, we as an audience can’t help but follow our own paths of attachment, our own personal desire, joy, pleasure, and shock.

Whether that is fascination in looking at the double portraits of men in Hill End and Bathurst from the late 1800s, pleasure watching Liam Benson dance, wonder at the drama of a gym-junky twelve-armed bodhisattva Owen Leong, curiosity around the serendipitous trajectories of art history in the found photographs of Casa Susanna—a 1960s New York retreat for cross-dressing heterosexual men, or simply being enthralled by a naked runway show. This is one trajectory of attachment.

A conversation I overheard in the gallery illustrates a more expected form of attachment. Two young women met their friend who was already making her way through the exhibition: ‘The reason why we came is ‘cause we saw your snapchat story … we were like, “Let’s go see some dicks!”’ A reason enough for many. Understandably so.

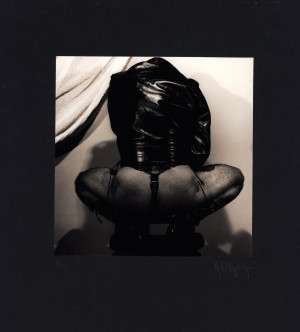

The nude bodies, hard and soft cocks, bulges, and fetish wear that make up only part of the show must, for some, loom large. The repeated warnings, first relayed by the gallery attendant and then reinforced in signage on the walls and catalogue, mark out the shifting terrain of public attitudes to homosexuality generally and explicit sex specifically. This is a shifting terrain that flows through the exhibition. Off the main gallery space is a room barred by a glass door with an R18+ restriction. The cordoning off is due mainly to Jean Genet’s 1950 film Un chant d’amour (A Song of Love). The film is a story of sex and intimacy between male prisoners that is, by today’s standards, sexually mild. But the R18+ label is applied for the tones of sexual violence that come with the prison guard and his gun. The room also houses two images from Robert Mapplethorpe’s controversial X Portfolio documenting parts of the BDSM scene: the leather-clad Helmut N.Y.C, the infamous bullwhip Self Portrait N.Y.C and Joe N.Y. C (all 1978), which depicts a person in full latex bondage gear (commonly called a gimp suit). Among the other works in the room are Tress’ Dockside Interview and Andy Warhol’s polaroid Untitled (Victor Hugo’s penis) (date unknown), the biggest penis in the show.

Censorship and controversy are not confined to this one room. Another Tress photograph, Bob Leet with Sheep, S.F. (1974), was momentarily stopped by Australian Customs and Border Protection Service due to its possible representation of bestiality. This put the show, and the rest of the incoming images, on Custom’s radar. The sheep in question was a toy sheep meant to represent the weight of nightmares. To commemorate this Customs kerfuffle, a small stuffed sheep is available for purchase in the Gallery gift shop.

Other invocations of censorship bring joy to resistance. Kalup Linzy’s video work Lollipop (2006) has Linzy and Shaun Leonardo lip sync to the eponymous song, banned from radio in the 1930s for the sexual suggestiveness of its lyrical banter. Linzy revels in this suggestiveness and takes it to a wonderfully gay level.

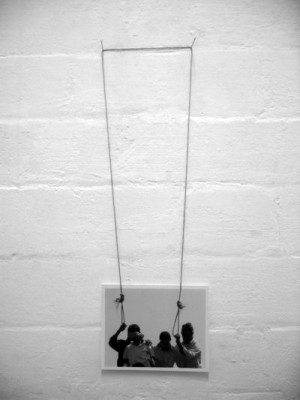

The show traces how some things have changed and how some things have not. One of the most affective works in the show is Luke Parker’s Double Hanging (2005). The work is a small photograph documenting the 2005 public hanging of two Iranian youths, Mahmoud Asgari (16) and Ayaz Marhoni (18). The photograph is hung on the wall with a thin cotton string that aligns with nooses about to be fitted over the youth’s heads. The work is pared back but high impact.

The hanging has been used to signal the Middle East’s treatment of homosexuals generally and Iran’s specifically—a dire and continuing situation across the region and many other parts of the world. Conflicting reports circulated widely around the case with Outrage! (British LGBT rights group), fulfilling a necessary role for the international community, decrying the hanging as state sanctioned homophobia. Human Rights Watch alternatively looked at sources that suggested the teens were convicted of the rape of a younger teen, held for 14 months and lashed before being hung. This later scenario still demands international attention but that of a different register. Double Hanging draws attention to widespread violence faced by queers around the world. It simultaneously indexes the international flow of images as well as the complex and unequal way of looking at those images, masculinities, and homosexualities. The work here, together with Benson’s photographs The Executioner, The Crusader, The Terrorist (all 2015), illustrate how the threat of violence and the connected dangers of social stereotype and stigmatisation continues to infuse our contemporary moment and circulate through images.

The relay between international photography and local cultures is repeated throughout the exhibition. Many images specifically document New York as a site of production and representation, as well as a site resonant in a global gay imaginary. Tress’ Dockside Interview, for instance, represents the NYC piers that for many years saw a thriving public sex culture. Spaces that, along with the area around Times Square, would be ravaged by city redevelopment strategies in the 1990s. Charles Atlas’ video work Mrs Peanut Visits New York (1999) follows Leigh Bowery as he walks the streets of New York decked out in signature high club kid drag (look 27 to be exact). Bowery pounds the streets, owning them. A car literally stops in the middle of the road to ogle Bowery in the rear-view mirror. Bowery struts up and past the car. These are representations of New York that have political efficacy and find importance in documenting the central role and reach of U.S. based visual cultures.

The danger becomes over-centralising the U.S. LGBTIQ experience. Gary Carsley’s work YOWL (2017) commissioned for the show, for instance, uses the rambles (a well-known gay beat in Central Park, N.Y.) as the backdrop for a lip syncing bust of Socrates reciting parts of Howl, Allen Ginsberg’s famous beat poem from 1950s San Francisco, while Warholian flowers and the script ‘please masters’ surround the scene. New York meets San Francisco meets Warhol—all important sites of queer attachment throughout the exhibition, but ones that don’t necessarily need to be restated.

Any show that casts such an admirably wide—yet specifically thrown—net around a symbol as loaded as ‘the male figure’ will invariably have some holes. Continuing the theme of looking by attachment it is also unsurprising that other Australian artists, international places, and photographic traditions seem to be waiting in the wings.

More generally, inclusion of trans masculine artists and representations would bring the role of photo media further into the contemporary moment. It is interesting, for instance, to imagine photographs or video generated through Cassils performance work throughout the exhibition, not in the section titled ‘Trans-ition’, but more fittingly in sections on classical or active bodies. The parameters of the exhibition—a focus on gender, the male figure, and LGBTIQ experience drawn together in an international context—sanction a broader account of bodies and gender identities not tied to those assigned male at birth. This absence among the many threads of masculinity and maleness engaged throughout the exhibition speaks to a particular way of looking, a particular attachment, and, perhaps, a particular generation.

Getting to Bathurst from inner Sydney is about a 3-hour drive. Many people can’t or won’t make that trip. The Unflinching Gaze brings together over 200 works that will unlikely ever be shown together again. The specific photo media trajectories brought together—in terms of the medium itself, the artistic and cultural generations they reflect, and the institutional landscape behind the exhibition—is definitely something that deserves a second thought; whether that be for pleasure, for politics, or for push-back. It is worth the drive.

Richard Perram OAM, ‘I’ve looked on beauty so much…’ in The Unflinching Gaze: photo media & the male figure curated by Richard Perram OAM (Bathurst: Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 2017), exhibition catalogue, 9.

Biographies

Paul Kelaita is a PhD candidate in the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies at the University of Sydney. Paul’s PhD research is focused on queer art practices in suburban Sydney. He completed his honours research at COFA, UNSW on photography, Australian masculinities, homosociality, and national identity in the work of William Yang.